Considering Internet traffic, lay publications, and peer-reviewed clinical studies, parents are confronted with the angst that their young child’s brain, undergoing surgery, may experience neurocognitive toxicity due to our anesthetic drugs. It is a natural next step to ask about the potential risks pediatric general anesthesia poses for the developing brain. How should CRNAs address their concerns?

Table of Contents

- The FDA sent out a warning

- The remarkable human brain and all those neurons

- Neurotoxicity – a concern in the age of wobbly information

- Major outcome studies in pediatric neurotoxicity

- Explaining pediatric general anesthesia risks to anxious parents

In the March 2022 issue of the journal Anesthesiology, a paper by prominent voices in pediatric anesthesiology entitled “Anesthesia and developing brains: unanswered questions and proposed paths forward” appeared. Another paper of equal stature in the icons of medical science from across the Atlantic Ocean, the British Medical Journal, asked, “Does general anesthesia affect neurodevelopment in infants and children?”

Along the way, also from across the pond, a disturbingly worded paper appeared in the British Journal of Anaesthesia: “General anaesthesia, the developing brain, and cerebral white matter alterations.”No one likes having their brain “altered,” so the possibility reflected in the title gave us a modicum of angst.

The FDA sent out a warning

These recent works come to us after a concerning December 2016 FDA Drug Safety Communication. This was a formal warning that anesthetics that bind to GABA and NMDA receptors used in those younger than 3 years old and pregnant women during the 3rd trimester may negatively affect the child’s brain. The warning was repeated later with somewhat more concerning language, which we truncate for brevity:

The FDA is notifying the public of changes in our previous warning about the use of general anesthetics in children, these include:

- Exposure to these medicines for lengthy periods of time or over multiple surgeries or procedures may negatively affect brain development in children younger than 3 years.

- Additional concerns about pregnancy and pediatrics describe animal studies that show exposure to general anesthetic and sedation drugs for more than 3 hours can cause widespread loss of nerve cells in the developing brain.

The warning involves at least 11 drugs we commonly use that bind at GABA or NMDA sites, including all anesthetic gases and our IV agents propofol, benzodiazepines, ketamine, and barbiturates. And we are not only being “warned” about using drugs affecting multiple receptors in young children but also in patients during their third trimester. If this is the case, one is left to wonder if there should also be a concern during the second or even the first trimesters. We get this issue with synaptogenesis, but if there is a legitimate concern, should it be broader? How much, or rather how little do we actually know?

The remarkable human brain and all those neurons

The human brain is wondrous, composed mostly of water (~75% by weight), and everything else being fat or protein. When removed from its bony enclave at fresh autopsy, it feels like soft tofu in one’s hands (which we have done; we advise using both hands!). As described to us by neurosurgeons, a bit of brain cortex about the size of a grain of sand may contain over 50,000 neurons, each creating well over 5,000 synapses. With almost 20% of the cardiac output going to the brain and a disproportionately large energy utilization, especially early in life, this organ is vital and darn expensive to run! The expenditure is so great in infancy that it may explain why infants generally sleep 14-20 hours each day!

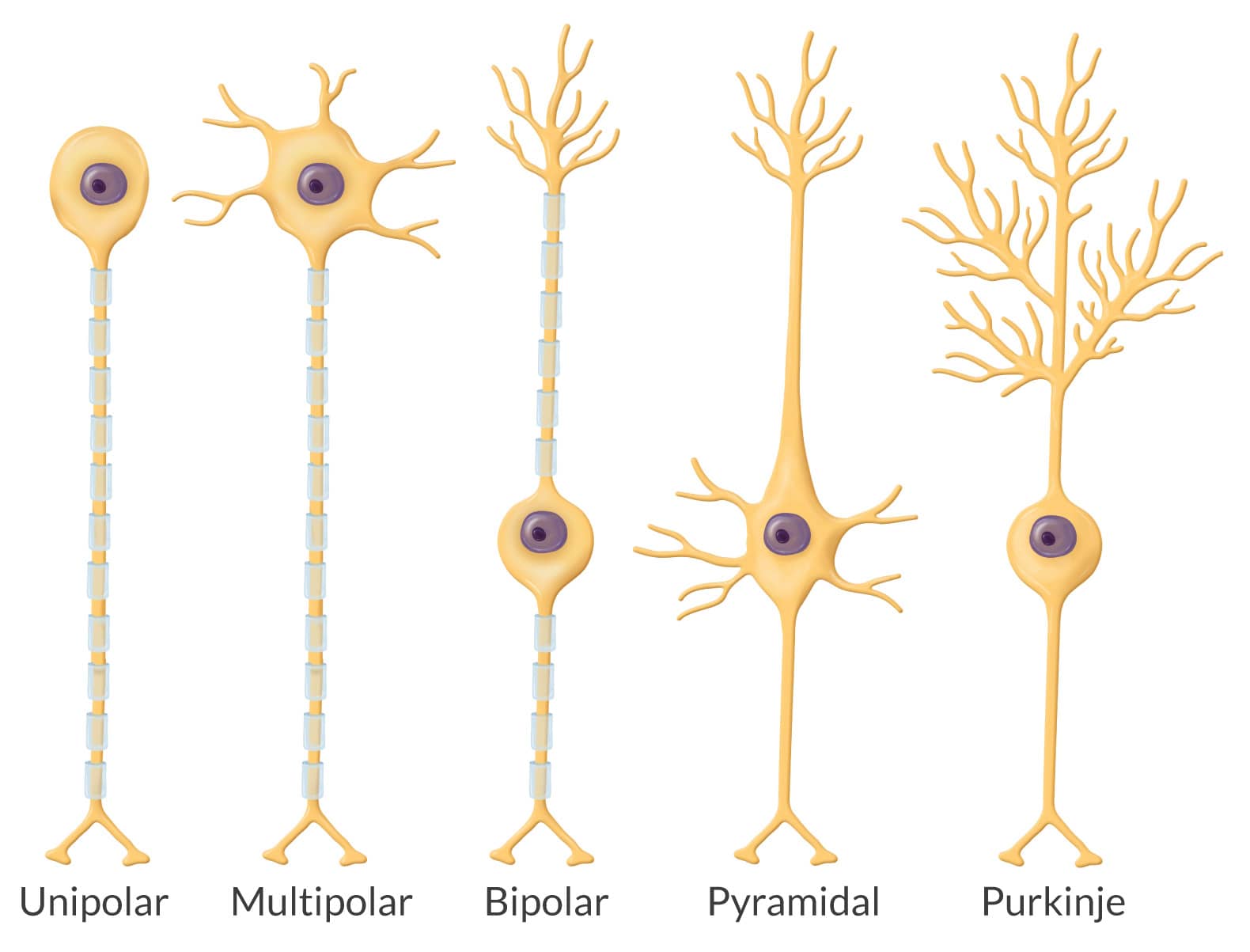

A neuron is unlike anything anywhere else in the body. Neurogenesis and synaptogenesis start in “embryo-hood,” proliferating at a rate rivaling blood cell genesis, peaking in about 3-4 years. Adults may have 86 billion neurons of 5 different types: unipolar, pyramidal, multipolar, bipolar, and Purkinje. The cell body and its long axon with tiny telodendria at its end look alien, menacing, yet paradoxically vulnerable. With their dendritic extensions, our brains harbor trillions of synapses. While the adult blood-brain barrier keeps neurons safe, the young child’s barrier is immature and permissive to toxins.

Neurotoxicity – a concern in the age of wobbly information

When seeking relationships involving biological phenomena, it is common for some to suggest cause-and-effect relationships even though there may only be an association at work. In contrast, others find no relationship at all. The temperature in the room can rise significantly among providers (e.g., CRNAs) and policymakers (e.g., the FDA) when discussing the risks and benefits of pediatric general anesthesia. For example, many hold tenaciously to one view, with little potential to move the needle even when reasonable contrary evidence is brought to the debate.

It is now common, armed with information and disinformation that spreads instantly and widely across the Internet with a single keystroke, for parents to ask if our anesthetic will harm their young child’s brain. They’ve likely heard of the FDA’s warning, with many having thoroughly researched it. What should we say to an anxious parent?

Major outcome studies in pediatric neurotoxicity

The first preparatory step is to consider the literature. Besides the risks demonstrated in animal studies, let’s briefly consider a few of the more prominent and elegant studies on humans performed worldwide:

- GAS (General anesthesia vs. spinal in young children). Here, 722 infants in over 20 centers worldwide who underwent inguinal herniorrhaphy were randomized to receive sevoflurane or an awake spinal anesthetic along with a sugar-coated pacifier. There was no difference in neurobehavioral outcomes at age 2 or 5 years.

- MASK (Mayo Anesthesia Safety in Kids). Neurobehavioral testing was performed in 411 controls (no anesthetic), 380 had one anesthetic, and 206 had multiple anesthetics. There was no difference in IQ testing among the groups, and processing speed and fine motor function were decreased slightly in those who received multiple anesthetics. Parents of those receiving multiple anesthetics reported more behavioral issues.

- Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. This prospective study grouped 13,433 children by none, one, or multiple exposure to general anesthesia before their 4th birthday. Motor, cognitive, language, educational, and social assessments were performed at ages 7 to 16 years using school exams, parent/teacher questioning, and in-person visits. There was no evidence of clinical neurotoxicity, but poorer motor and behavioral issues were seen in those exposed to multiple anesthetics.

- PANDA (Pediatric Anesthesia Neurodevelopment Assessment). To control for genetic factors, this crafty study published in JAMA, included children younger than 3 years who were siblings, one of whom had one anesthetic exposure, the other who had no exposure. Follow-up was at 8 and 15 years assessing neurocognitive function. All 105 sibling pairs were ASA I or II and no neurocognitive differences were found between the sibling pairs.

- Columbia University Longitudinal Study. Using Texas (25,855 children) and New York (16,843 children) enrolled in Medicaid, matching pairs, similar in attributes and all <5 years, were grouped by those who received one general anesthetic and those unexposed. Using ADHD medication prescriptions as the outcome, those receiving anesthesia were 37% more likely to require persistent drug treatment for ADHD.

Getting at the ‘truth’ regarding anesthetic-induced neurotoxicity–if there even is a single ‘truth’ –is dauntingly complex. It’s like attempting to quantify biodiversity. The National Geographic Society reports over 8 million species on Earth, yet only about 1.2 million have been identified. The task is Sisyphean in nature, as even the definition of “species” is in flux. The deeper one looks, the more jaded a single ‘truth’ becomes. Such is the case with anesthetic neurotoxicity, where trying to separate direct drug effects from comorbidities, inflammation, hypo- or hyperoxia, dysthermoregulation, pain, surgical trauma, nutrition, and illusive genetic influences greatly complicates definitive conclusions. There is also the nontrivial factor of drug dose and the timing of exposure relative to the child’s development.

Then we must ask, as with defining a species, what exactly constitutes a neurotoxic outcome? ADHD? Lower IQ? Slower reading comprehension? Poor social behavior? Parenteral perception of the child’s interactivity? The challenge to arriving at an absolute truth is considerable.

Explaining pediatric general anesthesia risks to anxious parents

Approximately 2 million pediatric patients undergo general anesthesia each year, a good portion of which are < 1 year of age. The risk involved in requiring general anesthesia is wedded to the individual child’s attributes and their procedure. Based on the many studies available, the concern is extremely low for a relatively healthy 3-year-old having surgery lasting less than 3 hours; the risk being virtually unmeasurable for one brief anesthetic. Concerns about neurotoxicity with general anesthesia and surgery increase somewhat when the exposure exceeds 3 hours and the child has undergone more than one anesthetic. The primary concerns are a higher incidence of ADHD, mild learning deficit, and behavioral issues. As is usually the case, the surgery is necessary and time-sensitive, and postponement is unlikely, especially where congenital anomalies threaten well-being.

That said, available clinical research has changed many surgeons’ practices, with new information influencing the timing of surgical intervention. Reconstructive surgery, plastic surgery, certain urological, and other surgeries for conditions that do not immediately impair life and function are often postponed until the child is older. Some authorities express concern that the FDA warning may cause unnecessary delays in surgical and diagnostic procedures, paradoxically resulting in adverse outcomes.

Remember, like major league pitchers with more than just a fastball in their repertoire, we have options. Regional anesthesia, including neuraxial and area-specific blocks, is available in some settings and for some procedures that may obviate the need for general anesthesia entirely.

We want to end on a remarkable, brand-new, first-of-its-kind human randomized clinical trial design published in 2024 in The Lancet. It involved repeated general anesthesia exposures in vulnerable young children in the multi-site Australian Cystic Fibrosis Bronchoalveolar Lavage study. We believe this is an important study because it gets to the heart of a contentious, concerning, and lingering issue in pediatric anesthesia: the notion of anesthesia causing adverse neurocognitive and behavioral effects in the very young.

The methodology was robust and exacting and the paper underwent extensive critique by authoritative referees on both sides of the issue. We will leave you with the authors’ conclusions: “These findings suggest repeated general anesthesia exposure in young children …is not related to the intellectual quotient, executive function, or brain structure compared with a group with fewer and shorter cumulative anesthesia durations.”One expert reviewer suggested it’s time to stop chasing the ghost of anesthesia causing neurocognitive impairment.

Addressing parents’ concerns and questions about neurotoxicity—now part of the routine consent process in some institutions—should be evidence-based, empathetic, and reassuring; certainly, don’t be alarming! From the outset, parents face angst in deciding if their child should undergo surgery and anesthesia. Emphasize that their child is in exceptionally good hands and that your absolute priority is their child’s safety.