Ketamine has experienced a renaissance from the drug’s initial use many years ago. Not only as part of a multimodal component of many anesthetic approaches to reduce opioid use but more recently as a drug to manage emotional and psychiatric issues. As nurse anesthetists, we have a responsibility to understand where we are with ketamine, especially as we consider its use in ambulatory “ketamine clinics.”

Table of Contents

- Ketamine and the fruit fly

- The remarkable clinical resurgence involving ketamine

- Clinical considerations

- Clinics are proliferating

- S-ketamine (marketed as Spravato®)

- Psilocybin—the magic mushroom

- Where are we with ketamine?

In October 2023, the popular “Friends” actor Matthew Perry, who acknowledged drug and alcohol problems for many years, was found dead at his Los Angeles home. The attending coroner cited his death as multifactorial but primarily due to “the acute effects of ketamine.” Perry was undergoing ketamine infusion therapy, but his autopsy revealed the fatal episode was not related to his most recent therapy session, which occurred 10 days before his death. Perry’s death aroused and focused widespread public attention on ketamine infusion clinics as well as microdosing of other CNS-targeting agents like psilocybin.

What is the clinical status of ketamine and other CNS-altering compounds like psilocybin for treating mental health issues? And what do we know about the many CRNA-managed, free-standing ketamine clinics that have emerged nationwide?

Ketamine and the fruit fly

You should not be surprised that the lowly fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, has taught us a thing or two about how ketamine works, given the remarkable legacy of the fly in genetic and pharmaceutical research. What’s known is that many of the drugs currently used to treat depression and anxiety act by altering CNS serotonin levels. Fruit flies conveniently use serotonin as a central transmitter, providing us with a surprisingly valid model to study its effect on the brain. There is even a mutation, dSERT (Drosophila serotonin transporter), that researchers used and just published in the highly regarded Journal of Neurochemistry, demonstrating that microdosing ketamine does not block serotonin reuptake but rather causes complex behavioral changes mediated by glutamate and serotonin receptors.

Now, that might not seem like a huge deal to the uninitiated. Still, it reveals what is being seen clinically by providers and patients alike—that ketamine, and likely other compounds, may work to alleviate depression by mechanisms previously unattainable by our existing pharmacopeia.

Similarly, recent work demonstrates that ketamine, an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, may revolutionize the treatment of depression because of its potent, rapid-onsetting, and sustained effects to relieve depressive manifestations. Of course, this has created a bit of a conundrum as the elimination half-life is briefer than its effect in relieving depression. There is still a lot to learn about how ketamine works to alleviate mental health issues–which we have a responsibility to do.

The remarkable clinical resurgence involving ketamine

For CRNAs who have been in practice for over 20 years, the movement to use ketamine to treat depression, PTSD, and even bipolar conditions in free-standing clinics owned and operated by CRNAs likely comes as a remarkable renaissance. Synthesized as CI-581 in 1962, it was widely used as a veterinary anesthetic. Its analgesic potency, preservation of sympathetic tone and airway reflexes, and its unique dynamics in creating a dissociative anesthetic state led to human use, marred by its tendency to cause emergence delirium and other unpleasant states of mind. With few exceptions, ketamine departed from routine clinical practice until it was resurrected as part of a multimodal, opioid-sparing analgesic technique, which coincided with incidental observations that it could sometimes remedy depression.

Clinical considerations

Many CRNA clinical entrepreneurs have subspecialized in the treatment of depression and related conditions using therapeutic microdosing of ketamine in free-standing clinics. The impetus came from U.S. studies, favorable case reports, and international publications. This body of animal and human research demonstrates that ketamine is often effective in treating major depression, bipolar disorder, and acute suicidal ideation. The careful titration and only moderate degrees of receptor occupancy can be advantageous to achieve its depression-relieving effect and avoid dissociative and psychomimetic activity.

In an August Up-to-Date, the authors noted that randomized trials of IV ketamine for treatment-resistant depression have traditionally occurred in academic settings with collaboration among expert providers. However, they acknowledge that freestanding ketamine clinics are now common, with treatments dispensed by providers who often have limited to no experience in treating depression, which they consider concerning. They also note that many patients are now treated with oral ketamine taken while at home and without a certified provider present.

The Up-to-Date authors note that ketamine is an NMDA receptor antagonist but emphasize that it is not clear whether this produces its antidepressant effects. Trials revealing that racemic ketamine was not as effective as its stereoisomer, S-ketamine, illustrate this point. Clinical and bench research suggests that ketamine may activate other brain components or increase connectivity among brain components.

Ketamine’s optimal delivery method has not been established. While most of the published work—and apparent use in free-standing clinics—involves IV administration, it can also be given intramuscularly, intranasally, orally, subcutaneously, or sublingually. Dosing and administration methods vary considerably among the providers offering the service.

We logged onto several CRNA-managed sites and learned about their services. There are even ketamine infusion clinic courses available for purchase; two that we visited, each offered by a CRNA, are a one-stop shop for what you need to know. They introduce what constitutes a clinic, how to set one up, what the indications are, how to administer the drug and the evidence for the treatment. Dosing strategies vary considerably, as noted in the Up-to-Date article, as there is considerable debate about what constitutes the best-evidence approach for a given patient.

One of the websites we visited has a chatline person ready to answer any questions (we did not ask any) and has in bold lettering, “Becoming a ketamine therapy provider will allow you to earn a high income, reclaim your schedule, and help patients.” A testimonial by one CRNA clinic owner/manager reported that his previously exhausting clinical schedule in his OR job was now rewarded by a practice that provided him with a better work-life balance.

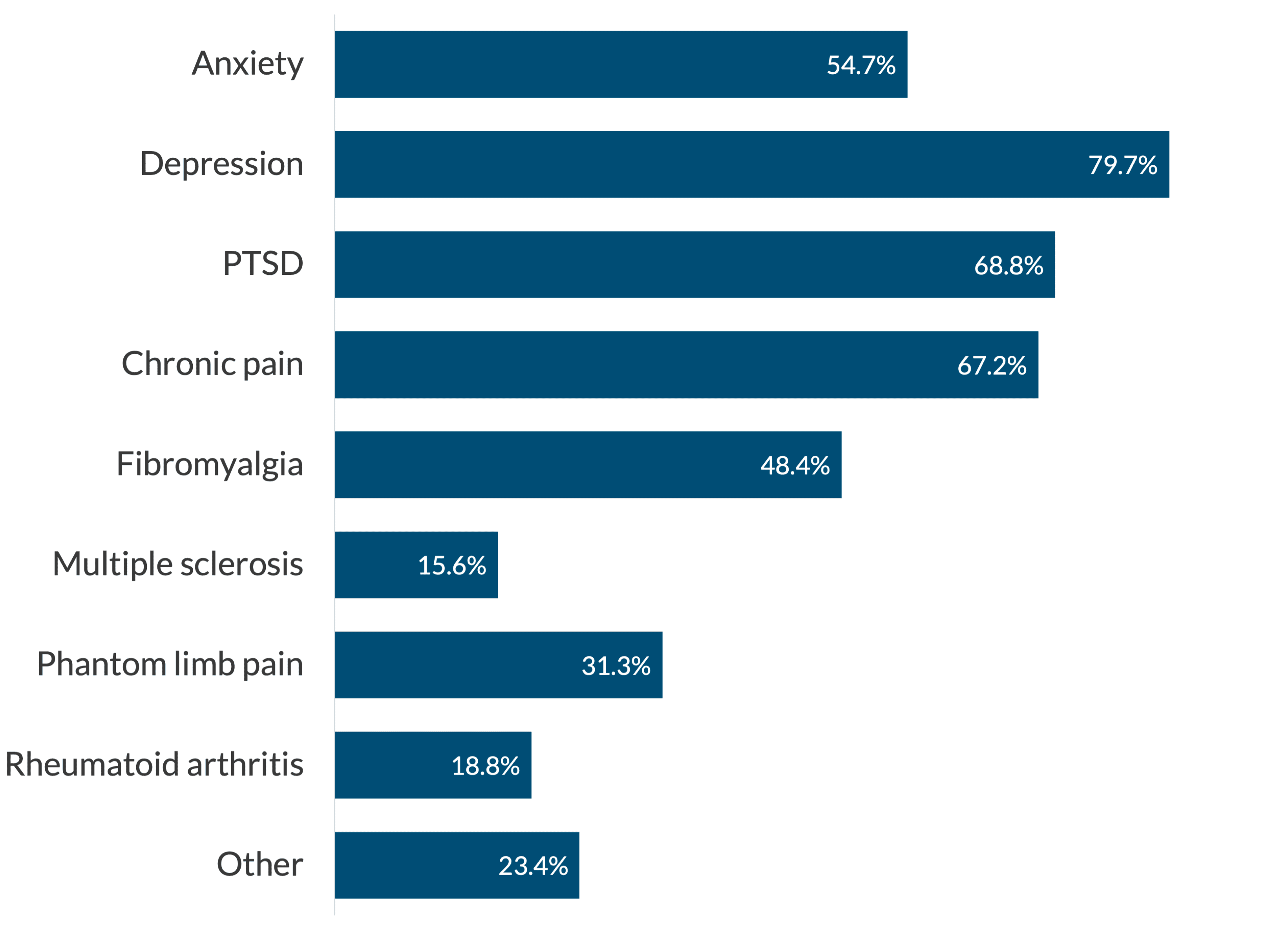

The AANA maintains a website dedicated to ketamine infusion clinics and offers relevant information and guidance for the interested. One of the many areas covered includes responses to a multi-question survey of CRNAs who provide infusion services. Regarding the question of: “What is the patient’s diagnosis being treated with ketamine infusion therapy,” these were the responses:

The “other” diagnosis included TMJ syndrome, cancer pain, migraine headaches, new onset daily headaches, post-Lyme disease, neuropathic disease, obsessive-compulsive disorder, gambling addiction, postpartum depression, bipolar disease, and high opioid use. A remarkably diverse group of conditions!

Clinics are proliferating

Our research found that the role of the CRNA, or other “elite nurse practitioners,” as one website refers to the providers, is defined by each state’s Board of Nursing Scope of Practice, which varies regionally. It is impressive that the number of clinics continues to increase, apparently in response to an escalating demand for their services.

With the number of clinics skyrocketing, there are cautions by authoritative figures concerned that it is an unregulated industry with the potential for misuse and patient safety issues. Ketamine is an FDA-approved drug that is increasingly prescribed off-label. There are concerns that its use in this domain may be jumping ahead of the evidence, with patients receiving treatments that have not been well-studied, validated, or guided by multidisciplinary consensus committees. Smita Das, MD, PhD, is one of many mental health experts we encountered who raised concerns. Dr. Das, a Professor of Psychiatry at Stanford University, chairs the American Psychiatric Association’s Council on Addiction Psychiatry and is vocal in urging caution. Consider too, that the treatments can be expensive, up to $1,000.00 per session, and are generally not covered by insurance.

S-ketamine (marketed as Spravato®)

S-ketamine, or esketamine, is an enantiomer of ketamine hydrochloride. Think of it this way: an enantiomer is one of a pair of non-superimposable molecules, mirror images of each other. A good illustration of this is by looking at your hands. While they are essentially mirror images of one another, they cannot be superimposed.

Esketamine has greater potency than ketamine. It is not used as an infusion but as a nasal spray under direct medical supervision. The FDA issued a boxed warning (its highest safety warning) for Spravato® because of potentially serious adverse events, including significant anesthetic effects, respiratory depression, and extremely high abuse potential. It appears to be available only through a special restricted distribution system, the FDA’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy. It is only administered in certified medical offices where specified monitoring strategies are used.

Esketamine is used far less frequently than the traditionally marketed ketamine hydrochloride. The free-standing ketamine clinics appear to be taking a more conservative approach to treating depression on an ambulatory basis until more evidence emerges about the safety and dosing of esketamine.

Psilocybin—the magic mushroom

Psilocybin is a tryptamine derivative that enhances CNS serotonin levels and is now approved for select clinical trials for treating treatment-resistant depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and suicidal ideation. Psilocybin comes from the Psilocybe and Panaeolus species of what are commonly called “magic mushrooms.” The four-part Netflix series, “How to Change Your Mind,’ based on the journalist Michael Pollan’s book, ignited a lot of public attention on microdosing to treat depression and enhance conscious experiences.

The saga of psilocybin is a rapidly evolving story, what some refer to as “the psychedelic renaissance.” The growing experience with psilocybin adds to an ever-enlarging pool of clinical and patient safety data relevant to treating mental health. Legal guidelines and frameworks are currently being revised for this Schedule I compound. Some cities (like Oakland, CA, and Washington, DC) soften their criminalization, while other locales (like California and Oregon) provide state-wide legalization.

The National Drug Intelligence website has this posted: “Psilocybin is illegal. Psilocybin is a Schedule I substance under the Controlled Substances Act. Schedule I drugs, which include heroin and LSD, have a high potential for abuse and serve no legitimate medical purpose in the United States.” Some states and cities have enacted legislation challenging this stance.

Psilocybin has hallucinogenic effects and is available in natural and synthetic forms. There is a growing interest in its use in treating addiction, depression, anxiety, alcohol abuse, PTSD, and several emotional and psychological conditions. Its legal status and guidance regarding its use to treat emotional and physical infirmities is very fluid.

A brief note about MDMA

Lykos Therapeutics spent a great deal of effort, and money, to seek FDA approval of MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine), also called “Molly” or “Ecstasy,” for treatment of PTSD. On August 9, 2024, approval was denied by the FDA for this synthetic drug that has effects similar to stimulants such as amphetamine-like compounds. If MDMA had been approved, it would have been the first new therapeutic drug for PTSD in a long while and would have given Lykos full control of the agent for 5 years.

There were a number of issues that surfaced including faulty studies of its effectiveness and safety concerns. For now we will leave it at that, but rest assured we will be keeping this on our radar as further developments in the area emerge. Given Lykos’ interest in the agent, we suspect there is more to come!

Where are we with ketamine?

Although the marketplace is in flux, the latest administrative data suggests that as many as 750 ketamine clinics nationwide generate revenues well north of 3 billion dollars annually. The number of for-profit clinics will likely continue to increase given the wide range of identified conditions that some suggest the drug can treat. Revenue generation is projected to double within 5 years. This is somewhat concerning, given that the insurance industry has largely shown disinterest in covering the service.

The FDA has not approved ketamine for use in any mental health treatment, resulting in providers formulating their treatment strategies and interventions for off-label interventions. Esketamine is FDA-approved for “breakthrough therapy” when administered under close medical supervision. Given the variability among providers in how they use ketamine to treat an expanding range of conditions, we will likely see lots of activity in professional and lay literature as well as in social media. Equally likely is the attention it will catalyze in legislative and regulatory proceedings.

As CRNAs ourselves, we understand the challenge of fitting CRNA continuing education credits into your busy schedule. When you’re ready, we’re here to help.